West Chicago Fire Department in front of Turner Town Hall, which was the location of the first Fire Department, in 1908

Fires, Firemen and Fire Safety

A History of Firefighting in West Chicago

by Martha Joy Noble

Over the past decade, the City Museum has been working with a manuscript by local writer Martha Noble about the history of the fire department.

Sadly Martha passed away on August 17, 2014, before she saw the publishing of her hard work. We are happy to launch a preview of the book with a full publishing in 2022. The City Museum has worked to put local history photographs into the work and ensure it is available in a digital platform as well as available for on-demand purchase for a print copy.

If you have questions, please contact Museum Director Sara Phalen at sphalen@westchicago.org.

The Beginning: Firefighting in a Railroad Community

Dr. Joseph McConnell, an early Turner Junction settler, boasted in the 1857 A History of the County of DuPage, that "though our village now numbers only about five hundred souls it is a place of vast business energy and active life." 1

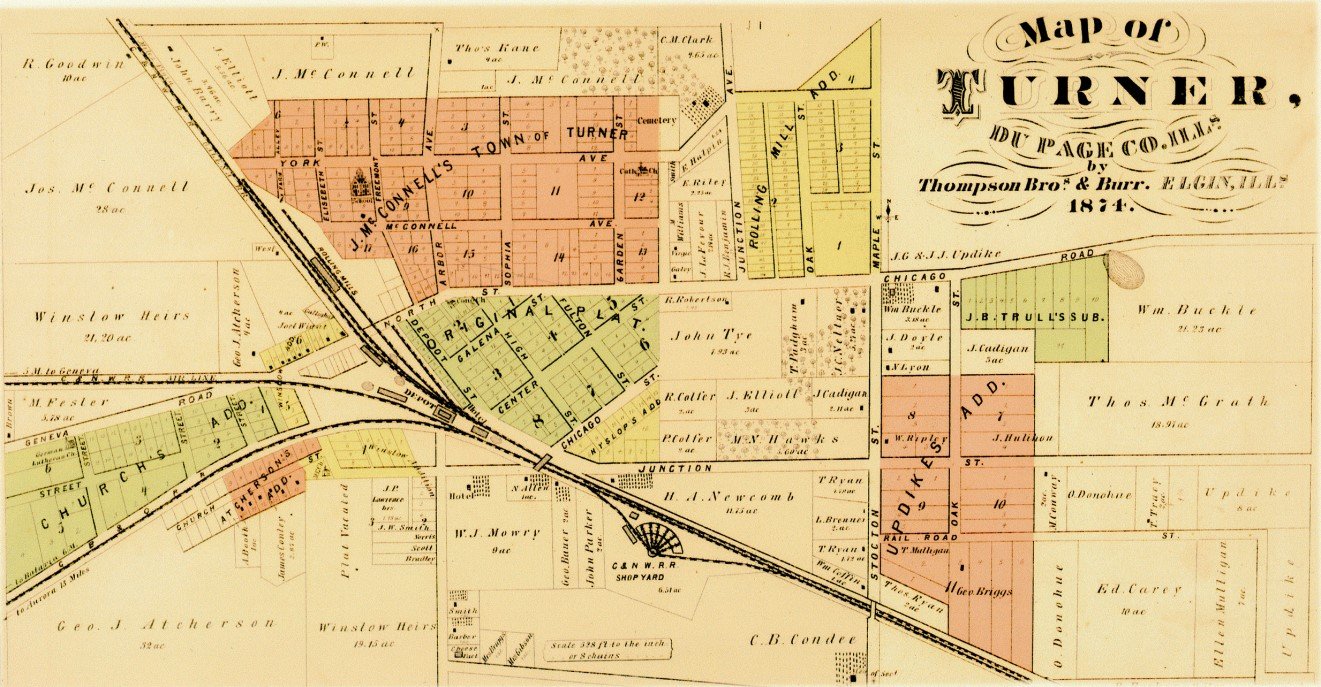

Earliest known map of Junction, 1850

But a fire at the wrong time could have destroyed the settlement. Almost forty trains came through Junction every twenty-four hours as the Galena and Chicago Union (G&CU), predecessor of the Chicago & North Western (now owned by Union Pacific), operated two main lines east from Chicago — one to Freeport and the other to Fulton. The G&CU had four wells to fill the tanks of their tenders, in addition to three woodsheds to supply fuel for the wood- burning engines. The 12-mile Aurora Branch Railroad, predecessor of the Burlington, also had its own woodshed and well at Junction. 2 Thus, the settlement grew up around the G&CU depot and featured a hotel, tavern, butcher shop, livery stable, general stores and a combination post office and grocery. The engine house and blacksmith shop were north of the depot.

In these early years, residents relied on the bucket brigade system to fight fires. Folks spread the alarm and ran home to get their 3-gallon leather buckets. They formed two lines of people from the fire to the nearest well or DuPage River branch. The men's line passed along full buckets and threw water on the flames. The empty buckets were handed back along a second line of women and children to be refilled. If a fire started in the middle of the night away from the village center, residents had difficulty getting to the blaze in time. Delay in getting to the blaze hampered firefighting efforts.3

Neltnor's first store

Merchant John C. Neltnor moved to Turner in 1865 after an apprenticeship with a druggist. His general merchandise store was known for its extensive stock of furs, gun powder, and farm machinery. Fire and explosion destroyed his uninsured store in 1869. "No one dared to go near it because of the gun powder," stated Marion Knoblauch editor of DuPage County: A Descriptive and Historical Guide, "and the inevitable explosion occurred."

Neltnor then opened a drug store next to merchant Casper Voll and finished building his Georgian style home at the corner of present-day Route 59 and Washington Street. By the early 1870s he established Grove Place Nurseries and a few years later published the Fruit and Flower Grower and Vegetable Gardner magazines. Neltnor suffered his second loss from fire when his new store and Voll's store burned in January 1876. He became editor and publisher of the DuPage County Democrat in 1889 and tirelessly advocated for a waterworks system and fire company, since he had firsthand experience of fire loss. 4

Since its founding in 1849 as Junction, the community had operated as an unincorporated settlement. In June 1870 the Naperville Clarion reported that Turner was "one of the most flourishing villages in the state," and historian Frank Scobey concluded "no doubt this prosperous condition was a major factor in incorporation of the Village of Turner three years later."5

Early Map of Turner, 1874

Forty-three men petitioned the State of Illinois for village organization, and signers included Thomas Evenden, John Lakey, John C. Neltnor, Frank Whitton, and Albert Wiant. Many of these signers — merchants, tradesmen, farmers, and railroad workers — played an important role in the growth of the village.6

Voters elected six business and civic leaders: Captain Lucius B. Church, Turner's highest ranking Civil War officer; Casper Voll, merchant; Albert H. Wiant, merchant; Lyman C. Clark, insurance agent; Frank Whitton, butcher; and Henry Bradley, grain, and livestock shipping businessowner, to serve as a board of trustees. The trustees decided, "…that the Seal of the Village shall have as a Design a Locomotive Engine surrounded by the words Village of Turner Incorporated July 12, 1873." 7 The village boundaries included 645 acres and 850 residents. As the 1870 unofficial population was 1,086 this meant that about 236 people lived in rural unincorporated Turner.

Town Hall, 1884

The two-story brick Town Hall on Main Street, built in 1884 (now the City Museum), had a double door that was wide enough for a fire wagon. The Town Hall housed the village council chambers and was used by the one-man police department. The Turner correspondent for the Wheaton Illinoian stated in May 7, 1886, that "the cost of Town Hall to date is $4,000. What an artesian well that would have furnished." 8 Four months later the paper reported that "the town hall is being finished off, that's the way the money goes; in the meantime the town is left to burn."9

The village nearly burned in May 1885 when sparks from a passing locomotive apparently started a blaze at the rolling mill that manufactured railroad frogs— sections of rails used for crossover tracks. The Turner Junction News (an edition of the Wheaton Illinoian published from 1871-1889) reported, "The lumber yard, steam mill, barns, and residences were all in danger. But with right good will the citizens turned out and the Bucket Brigade did good and efficient service. . .. Yet in spite of some of their endeavors fire found lodgment in several buildings, some of which took fire no less than six times."10 Construction of a new rolling mill began in June and was finished in August. The Turner Junction News reported that it was "built so as to greatly lessen the danger of fire." 11

During an 1887 drought, the Turner correspondent for the Wheaton Illinoian wrote that, "With no water supply, everything as dry as timber, waiting only for a match, and with strong winds to favor it, what a high old time a fire would have along the main street."12 Therefore, in July 1887 the Turner Board of Trustees earmarked funds for a village well and purchased 24 buckets, an extension ladder, 2 axes and grappling irons (anchor tools with 4 or 5 claws) to grab objects. Ten days later the trustees bought a four-wheel hook and ladder wagon "with all equipment from a Chicago firm."13 The men pulled their wagon to the fire. At the scene near a well or stream, six or more men worked the long parallel handles of the pump to build water pressure in time to the foreman's beat of sixty up-and-down strokes a minute. It was tiring, intense labor; often the men were exhausted by the time they doused the flames.14

Finally, the village president and trustees unanimously passed "An Ordinance Creating a Hook and Ladder Company," on April 2, 1888:

“That there be and is hereby established a Village Hook and Ladder Company in and for the Village of Turner to be known as the Turner Hook and Ladder Company Number 1, Which shall consist of one Captain, one Foreman, one Assistant Foreman and such number of other members as said Trustees see fit to approve of.”

The ordinance gave the captain "custody, subject to the discretion of the Board of Trustees, of the hook and ladder truck and all equipment belonging thereto."15

Yet the trustees appointed no captain, foreman, assistant foreman, or other hook and ladder company members. The trustees failed to plan or build a network of reservoirs, pumps, and pipes to bring in a water supply for firefighters. It was a fire department on paper only, with no men or water supply system.

Unknown bucket brigade (Internet)

Waterworks: Making Firefighting Easier

Despite an 1890 population of 1,506 residents and new factories along the Elgin, Joliet & Eastern Railway (EJ&E) suburban Chicago north/south route, the Village lacked a waterworks system. In 1890 the Chicago & North Western, successor to the Galena & Chicago Union ( and now owned by Union Pacific), built an artesian well near their shops for railroad use.16 The Turner columnist for the Wheaton Illinoian asked, "Would it not be well for the city fathers to watch progress of this undertaking and see if they cannot devise some way to give us fire protection." 17 By July 1890, citizens petitioned the Village Board to set up a Turner waterworks, but the board rejected the idea.18

Pioneer locomotive

A September 8, 1893, Wheaton Illinoian news item reported that no rain had fallen in Turner for nearly 80 days. During that drought, a fire at West's Store on Washington Street spread along the railroad tracks, exacerbated by dry grass and locomotive sparks.19 John C. Neltnor, who had lost two stores to fires, kept up his campaign for a waterworks. In his January 1894 DuPage County Democrat, he proclaimed that "the people of Turner, aside from a few non progressive old fogies, are unanimous for a system of waterworks."20 On August 4, 1894, fire destroyed three wood-frame Main Street buildings (now 126, 128 and 130) and The DuPage County Democrat headline read, "Turner's Big Fires."21

“… And it was indeed fortunate for the town that the fire occurred just where it did and that there was scarcely any wind, or a greater part of the business portion of our village might now be in ashes….

“Nearly the entire town was soon aroused and hastened to the scene of the fire. Much hard work was done but it was impossible to save the buildings ….

“The three buildings stood between the town hall and J. Fessler's, both high brick buildings, which acted as fire walls. But for these the damage would have been much greater…. The North Western engine men did much valuable service in the rear of the buildings, saving by their persistency, the company's freight houses and probably all the wooden structures from Carr's store to the lumber offices.”

A few days later, on Tuesday, August 7, 1894, fire destroyed the EJ&E depot. Agent J. Woodruff was "sitting in his chair at the depot … he became suddenly aware that it was getting uncomfortably warm under him, and glancing down saw that the floor was all on fire. He barely had time to get out before the floor fell in and in two minutes the whole building was enveloped in flames. The alarm was given but nothing could be done to save it …. The fire was probably caused by a spark from a passing engine blown under the depot."22

Citizens held a public meeting on the waterworks question the evening of the "J" (EJ&E) depot fire and appointed a committee to ask the village board to call a special election on a waterworks and city charter organization. Editor Neltnor of the DuPage County Democrat observed that "While we are heartily in favor of both, the water works is what we want now and want them badly." 23 The Village Board responded in September by forbidding any further construction of wood frame buildings on Main and Washington Streets. 24

Ninety-eight residents petitioned in October 1894 for a special election to issue municipal bonds to construct a waterworks system, but voters defeated the proposal by 32 votes.25 In January 1895, Shurler's tailor shop and an adjoining cottage burned, and the Turner correspondent for the Wheaton Illinoian reported as follows:

“The fire broke out in Shurler's tailor shop soon after 5 p.m. Monday. It seems to have been a fire similar to others Turner has been visited with — a volcano from the start.

“It was at once evident the cottage adjoining … was also doomed. In the course of an hour the foundations and burning embers alone remained….

“An interesting feature of the case was to see enterprising citizens of the corporate village of Turner sitting on the surrounding fences, like a flock of prairie hens cooling off their public spirit and prophesying as to the time when the business portion of the town will be swept away by fire; and these are the men who voted against water works.26

Once again many residents demanded action. But it was easier to call for waterworks than to make the sacrifice necessary to pay for the system. The DuPage County Democrat reported on February 1, 1895: "A call is always made after a fire and is considered the proper thing to do."27

Seven months later the village board passed an enabling ordinance for an October 15th waterworks election. The Turner columnist for the Wheaton Illinoian reported that "despite a good deal of opposition" voters approved the waterworks measure. The columnist said that "some citizens were evidently a trifle excited, threatening to sell out and leave town in case the measure carried. If they were in earnest, why the sooner they go the better it will be for the town."28

Village Board President W. T. Reed appointed W. J. Carr and A. E. Hahn to a standing committee on waterworks led by Dr. T. G. Isherwood. Committee members visited plants in Woodstock, Aurora, Batavia, and Downers Grove.29 The Village Board finally passed an ordinance in December 1895 to build a waterworks with a deep well, pump, and boiler house, including two pumping engines, surface reservoir, standpipe, and about 4 3/4 miles of cast iron distribution water pipes with 43 hydrants, 14 gate valves, and all necessary appendages. In 1896, the Village of Turner, newly renamed the Village of West Chicago, hired the S. T. Pope Company to build the water plant by July of that year.30

Before final tests of the system, Neltnor declared that the village had "material for a fine volunteer fire company."31 A May 1896 organizing meeting at the Town Hall produced the Hose & Hook & Ladder Company No. 1. In June, the Village Board named Matthew J. Leonard Fire Marshal. He delivered mail with horse and buggy on a rural route and was a crossing guard for the C&NW.32 Not long after, the Village Board ordered 600 feet of Maltese Cross hose at $1.00 per foot, one No. 23 cart (this cart was probably used to haul hose) at $95.00, two swivel-handle pipes at $7.50 each, and one dozen spanners (to open fire hydrants) at $3.00 per dozen. The board spent $713.00 on these purchases, which were delivered in July.33

Before their first official meeting, the volunteers sponsored a Fireman's Picnic on September 1st, 1896. The 22 items on the "cash paid out" report offered a glimpse of the festivities. The traditional picnic items, such as ice cream, soda, ball players, and music are listed along with payments for lumber, nails, and dray (horse cart) services. The gross receipts were $216.65 cash, and after the treasurer paid expenses of $120.73, the company had a $95.92 profit.34 Although the volunteer firefighters received a small stipend for fire calls that they answered, they always had to raise money for their helmets, coats, boots, and additional tools and equipment.

Hose Cart, West Chicago, circa 1918

Left to right Floyd Gridley, Henry Haack, Ralph Fairbank

Firefighters: Organizing a Volunteer Company

Now that the village had a waterworks system, a fire company, wagon and a newly appointed fire marshal, it was time to get some firefighters. Marshal Leonard called a meeting of the volunteers of the Hose Company and the Hook, and Ladder Company on September 11, 1896. The Hose Company elected postmaster J. H. Creager, Captain; Henry Fessler, First Lieutenant; and hardware merchant W. A. Boynton, Second Lieutenant. The Hook and Ladder Company elected merchant Charles Kruse, Captain, and painter/decorator Thomas Kirkland, Lieutenant. Treasurer Charles Kruse and Secretary Lester A. Wiant (proprietor of Wiant Brothers store) served both companies.35 Charter member W. A. Ball recalled that each man received an elaborate membership certificate. The document was signed by Village Clerk Dennis C. Ahern and Fire Marshal Leonard and printed by the Neltnor Publishing House.36

Membership changed over the next months as several charter members resigned. At their October meeting the firefighters approved a motion to keep track of attendance: members who missed three meetings would be notified. In January 1898 the men voted to print 200 cards to notify members of special meetings and fines. 37

The men called their meeting room Firemen's Hall and purchased three spittoons, linoleum flooring (from member merchant Fred Rohr), and a chair.38 As the men participated in practice drills and answered fire calls at all hours, they developed a unique bond among themselves. The bond was strengthened when firefighters and their leaders appeared before village trustees to plead for wagons, boots, and higher pay.

On May 10, 1897, a firefighter committee asked the village board for a fire whistle, 2 nozzles, and hose.39 In August another firefighter committee requested "four hundred feet more hose."40 Village Board minutes for August 7, 1897, record that "It was moved and seconded that we purchase 400 ft. Maltese Cross Brand 2 ½ inch hose and three 30 inch 7/8 nozzles and same to be paid out of one of the several appropriations already made."41 The first test of their equipment and drills occurred when the rolling mill, which had been rebuilt after the May 1885 fire, burned around 11:00 p.m. on October 5, 1897. Two minutes after the pumping station whistle sounded, Leonard and his men were at the scene. Their speedy response saved the building.42

The men decided at their December 6, 1897, meeting "that the Chief shall buy a horn and also a cap."43 The horn was probably a tin "speaking trumpet" used by officers to shout commands at the fire scene. The speaking trumpet has become a firefighting insignia — one trumpet for lieutenant, two for captain and crossed gold trumpets for chief — on their uniform lapels.44

In December, the Village Trustees set a pay rate of $1.50 when firemen responded to an alarm with the hook and ladder wagon and hose cart. 45 The hook and ladder wagon was often pulled by team horses from a nearby stable. The hose was wound on a large reel that was mounted on a two-wheel cart.

In addition to persistent requests for pay and equipment, the department wanted a village levy on foreign insurance companies (firms not incorporated in Illinois) so that each agency paid the village treasurer one percent of its annual gross receipts. The treasurer would then turn the funds over to the Fire Department and these funds would allow the department to purchase additional equipment that the village could not afford. At the January 3, 1898, meeting Captain Creager appointed a committee "to interview counsel about levying the tax on foreign insurance companies …." 46

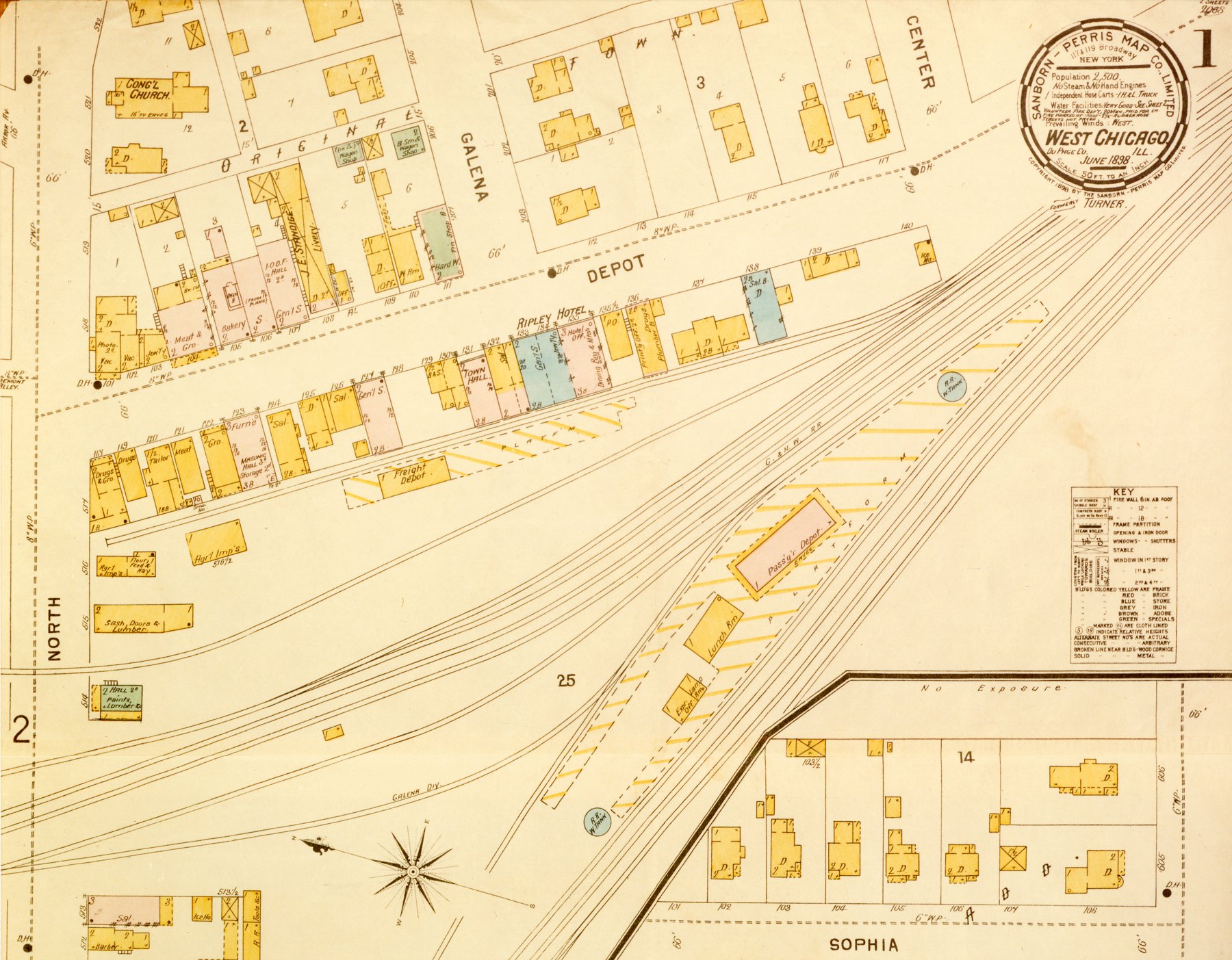

Map of downtown area showing building construction status and listing fire equipment availability. 1898

The Village Board passed an ordinance to tax foreign insurance companies for "the benefit of the West Chicago Fire Department." In August 1898, K. I. Neltnor reported $867.47 in premiums, and sent a check for $8.67 to the village, and A. Campbell listed $389.39 in premiums, and sent a check for $3.89 to the village.47 The village treasurer may have been slow to turn funds over to the department. In 1899 the men appointed Fire Marshal Leonard to lead a delegation to "interview village council in regard to money’s paid them by Insurance Company’s which should be turned over into the Fireman’s Treasury."48

The 1898 Fire Department Labor Day benefit entertainment at the Ball Park was "gotten up by our firemen, who never do things by halves," stated the DuPage County Democrat, and featured a ball game between the west side and east side businessmen, a two-mile bicycle race, and a firemen's relay race won by the hose men. "Six or seven hundred fun-loving people enjoyed the event."49 The treasurer reported net proceeds of $84.08 were added to $61.83 cash on hand for a grand total of $145.91 as of September 6, 1898.50

Still needing to raise their own money, Fire Company members decided to rent a hall and hire musicians for a dance held in March 1900. Each firefighter had to sell ten tickets. All members were required to wear their uniforms to the dance, and firemen led the grand march. The evening included a supper: "the ladies (perhaps wives and daughters of firefighters) met to arrange the supper."51

The men still needed better equipment. Leonard led a May 1902 delegation to a Village Board meeting "to see about another hose cart." The Naperville Clarion reported that West Chicago purchased a new hose cart in 1903.52 The hose cart was used at a September 7, 1904, afternoon fire at Standidge's Livery Stable on the east side of Main Street.

Donavin's Blacksmith Shop

When firefighters arrived, residents had formed a bucket brigade line while others aimed garden hoses at the flames. Wind carried ashes and sparks to the Odd Fellows Building, Springer & Rohr's Store, Donavin's Blacksmith Shop, offices, barns, and several residences. The men called the Wheaton Fire Department when the fire appeared to be out of control. Fortunately, a freight train had stopped in Wheaton, and the station agent loaded Wheaton fire apparatus and men on the train. The C&NW dispatcher gave the freight exclusive right-of-way, and they arrived 13 minutes later.53 The men sent the Wheaton Fire Department a "vote of thanks" for their prompt response.54

Three downtown fires threatened homes and warehouses during July and August 1906. A July 30 fire burned the Washington Street Wiant & Stephens Warehouse. An August 12 blaze destroyed the barn and equipment of house mover E. E. Belding. Five days later, sparks from an EJ&E engine probably started an early morning fire at the Factory Street Chicago Crossing Company, manufacturers of rail crossings, near the EJ&E tracks. The plant was ruined, but firefighters kept flames from spreading to nearby Chicago Heater Company buildings.55 Lightning destroyed the wooden steeple of St. John the Baptist Church in Winfield that afternoon; West Chicago and Wheaton hook and ladder companies aided the village bucket brigades. The Wheaton Illinoian said that …. "To their work is due the saving of the buildings about the church and perhaps the whole town."56

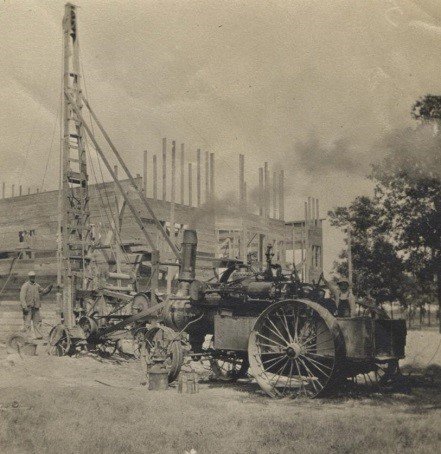

In August 1906 the village reincorporated as the City of West Chicago. In 1907, the City Council Fire and Water Committee hired Diebold Brothers to sink or drill another well on city property.57 The city issued waterworks bonds in 1908 and the next year authorized "an ordinance for a water supply pipe with hydrants, gate valves, tees, and all connections laid in Depot Street (now Main Street) to connect with the pipes on Depot Street and Maple Street (now Route 59)."58

Diebold Company Drilling Well

In addition, West Chicago had bought a set of extension ladders, a roof ladder, axes, and lanterns. The Northern Illinois Democrat editor commented in July 1907 that "They were badly in need of them, and although we have been fortunate in not having a blaze of any consequence for some time, it is well to be prepared for any emergencies. Our fire protection cannot be too good."59

Firemen, 1908

The population of West Chicago increased from 1,877 in 1900 to 2,378 in 1910. The Chicago, Aurora & Elgin electric interurban branch route service from Wells Street Chicago via West Chicago to Geneva began in 1909. The High Lake stop on the east side of the city that included present day Morningside, Sunset and High Lake Avenues was the "first significant stop."60

An October 10, 1910, fire at the McConnell Avenue Turner Cabinet Company, manufacturers of post office fixtures and equipment, caused about $50,000 to $60,000 worth of damage. (In 2012 figures the approximate amount is between $1,160,681.82 and $1,392,818.18).61 In A Brief History of an Old Railroad Town, Frank Scobey and Gerald Musich described the threat to the city: "when the city pumping station and only source of water, directly opposite the burning factory, caught fire three times in succession it was thought the business portion of West Chicago was doomed. But the engines were kept working in the burning station until the fire was out, when a shutdown was ordered for needed repairs."62

Waterworks and firefighters kept the business center safe from this fire but newer wagons and pumping equipment were needed to meet the increased population of the village.

Motorized Truck, circa 1918

Left to right: Ernie Norris, Ted McCabe, A.G. (Tony) Goetz, William Wagner, Charles Sproat, F.A. Goetz

End Notes:

[1] C. W. Richmond and H. F. Vallette, A History of the County of DuPage, Illinois; containing an account of its early settlement and present advantages (Chicago: Scripps, Bross & Spears, 1857), 164, http://books.google.com.

[2] Ibid., 165.

[3] Paul Ditzel, Fire Engines, Firefighters: The Men, Equipment and Machines from Colonial Days to the Present (New York: A Rutledge Book, Crown Publishers, 1976), 7, 20 and 64.

[4] Marion Knoblauch, ed., DuPage County – A Descriptive and Historical Guide. American Guide Series, Special Revised Edition (Wheaton, IL DuPage Title Company, 1951).154-155 and Scobey and Musich, A Brief History of An Old Railroad Town, 44.

[5] Scobey, A Random Review, 45.

[6] Scobey and Musich, A Brief History of An Old Railroad Town, 7.

[7] Scobey, A Random Review, 38.

[8] "Turner Column," Wheaton Illinoian, May 7, 1886. See also Scobey, A Random Review, 43-44.

[9] "Turner Column," Wheaton Illinoian, September 17, 1886.

[10] Scobey, A Random Review, 25. Information on the Turner Junction News found in Scobey and Musich, A Brief History of An Old Railroad Town, 49.

[11] Scobey, A Random Review, 25.

[12] Quoted in Scobey, A Random Review, 87.

[13] Scobey, A Random Review, 89.

[14] Ditzel, Fire Engines, Firefighters, 68.

[15] Village of Turner, Regular Council Meeting, April 2, 1888.

[15] Village of Turner, Regular Council Meeting, April 2, 1888.

[16] Scobey, A Random Review, 87.

[17] Wheaton Illinoian, "Turner Column," May 2, 1890.

[18] Scobey, A Random Review, 87.

[19] Scobey, A Random Review, 87.

[20] Quoted in Scobey, A Random Review, 88.

[21] DuPage County Democrat, "Turner's Big Fires," August 8, 1894.

[22] DuPage County Democrat, "J Depot Fire," August 8 1894.

[23] DuPage County Democrat, "Water Works," August 8, 1894.

[24] Scobey, A Random Review, 67.

[25] West Chicago City Council Minutes, October 6, 1894 and November 20, 1894. See also DuPage County Democrat, Village Board Proceedings," October 10, 1894.

[26] Wheaton Illinoian, "Turner Column," February 1, 1895.

[27] Quoted in Scobey, A Random Review, 88.

[28] Wheaton Illinoian, "Turner Columnist," October 18, 1895.

[29] Scobey, A Random Review, 88.

[30] City Council Minutes, December 7, 1895.

[31] Scobey, A Random Review, 89.

[32] Herb Carlson, "Tower Men and Guards," Press, August 14, 1980.

[33] City Council Minutes, June 13, 1896.

[34] West Chicago Fire Department Minutes, "Total Amount Cash Received from Fireman's Picnic on September 1, 1896," 120.

[35] Minutes, Fire Department, September 11, 1896, 10.

[36] Press, "Finds Interesting Relic of Early Days of W.C. Fire Dept.," September 12, 1929.

[37] Minutes, Fire Department, October 2, 1896, 12 and January 3, 1898, 25.

[38] Minutes, Fire Department, March 6, 1899, 37; April 1, 1899, 38; November 6, 1899, 49.

[39] Minutes, Fire Department, May 10, 1897, 18.

[40] Minutes, Fire Department, August 4, 1897, 20.

[41] City Council Minutes, West Chicago, Illinois, August 7, 1897.

[42] Scobey, A Random Review, 26.

[43] Minutes, Fire Department, December 6, 1897, 24.

[44] Paul Hashagen, "Taking Charge: The Evolution for Fireground Command," from The American Fire Service: 1648-1998, A special section from the September 1998 issue of Firehouse magazine on www.firehouse.com. A photograph of a speaking trumpet and helmet may be found at www.toledofiremuseum.com.

[45] City Council Minutes, West Chicago, Illinois, December 8, 1897.

[46] Minutes, Fire Department, January 3, 1898, 25.

[47] City Council Minutes, February 5, 1898 and August 20, 1898.

[48] Minutes, Fire Department, June 5, 1899, 39.

[49] DuPage County Democrat, "The Labor Day Entertainment," September 7, 1898.

[50] Minutes, Fire Department, September 6, 1898, 32.

[51] Minutes, Fire Department, February 12, 1900, 52, February 19, 1900, 53 and March 5, 1900, 54.

[52] Minutes, Fire Department, May 6, 1902, 86 and Naperville Clarion, August 26, 1903.

[53] Scobey, A Random Review, 111.

[54] Minutes, Fire Department, September 9, 1904, 115-16.

[55] Scobey, A Random Review, 116.

[56] Quoted in Louise Spanke, Winfield’s Good Old Days (Winfield, IL: Winfield Library Board, 1978), 123.

[57] City Council Minutes, September 16, 1907.

[58] City Council Minutes April 6, 1908 and September 7, 1909.

[59] Northern Illinois Democrat, "Equipment," July 18, 1907.

[60] Larry Plachno, Sunset Lines The Story of the Chicago Aurora & Elgin Railroad 1 – Trackage (Polo, Illinois, Transportation Trails, 1986) 137-139.

[61] http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl. Their records begin with 1913.

[62] Scobey and Musich, A Brief History of An Old Railroad Town, 47